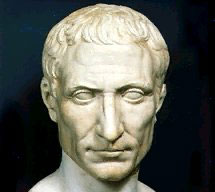

Dutch archaeologists have discovered evidence which finally proves Julius Caesar was in the Netherlands and fought in the Gallic Wars from 58 BC to 50 BC. Remains of the battle site were found close to the town of Oss in Brabant, the first battle site ever found in the Netherlands according to archaeologist Nico Roymans from Vu University in Amsterdam. As a result, for the first time there’s proof of Caesar’s actual presence there.

Dutch archaeologists have discovered evidence which finally proves Julius Caesar was in the Netherlands and fought in the Gallic Wars from 58 BC to 50 BC. Remains of the battle site were found close to the town of Oss in Brabant, the first battle site ever found in the Netherlands according to archaeologist Nico Roymans from Vu University in Amsterdam. As a result, for the first time there’s proof of Caesar’s actual presence there.

di Ginger Perales da ![]() del 15 dicembre 2015

del 15 dicembre 2015

Over the last 30 years researchers have been using archaeological, historical and geo-chemical methods to analyze a vast array of items unearthed at the site, including swords, a helmet, spearheads and skeletons. Carbon analysis of the bones has dated them as being from the last century BCE. This evidence combined with the weapons has confirmed the find is from the correct period.

The Gallic Wars were fought between Rome and at least two separate German tribes, ending with the decisive Battle of Alesia in 52 BC. While the Gallic tribes on the whole were considered to be an equal match militarily to the Romans, internal conflict between the tribes practically guaranteed Caesar’s victory.

With this victory and the resulting absorption of Gaul into the Roman Republic, (a substantial expansion) Julius Caesar had paved an easy path to becoming the sole ruler of Rome. Today, a majority of historians agree the wars were instigated by Caesar for the primary purpose of boosting his political career and paying off his considerable debts with plunder.

The Commentarii de Bello Gallico is Caesar’s own firsthand account of the battles which took place in the Netherlands and is still considered the most important and comprehensive account of the conflict. The six volumes include battle descriptions and war-time intrigues which took place during the nine years he fought the local armies that opposed Roman domination in Gaul – Gaul is generally considered to have included modern day Belgium, France and parts of Switzerland. In the Commentarii de Bello Gallico the Roman invasion of Gaul is portrayed by Caesar as a defensive and preemptive action.

Regardless of the personal motivations ascribed by historians, defeating Gaul was important to Rome in a military sense. Conquering Gaul provided Rome the means of securing a defensible natural border (the Rhone river) against its enemies to the north along the Rhine River, preventing ongoing attacks.

Meanwhile, in Rome Caesar’s contemporaries had begun labeling him a war criminal, guilty of perpetrating what today would be considered genocide, and many were promoting the idea of charging and trying him for these war crimes. Much of the talk was generated by stories coming back from the battlefield regarding Caesar’s unwillingness to offer refuge to Gaul natives (specifically the Helvetii). Some claims stated that after Caesar turned them away, he followed them back into Gaul, executing soldiers and slaughtering entire villages. The campaigns Caesar led against the Helvetii are described and defended in great detail in theCommentarii de Bello Gallicoaccusations.

The Helvetii were actually a coilition of approximately five related Gallic tribes living on the Swiss plateau, hemmed in by the Rhone and Rhine rivers and mountains. Because of the inhospitable landscape and increasing pressure from German forces from the north and east, by the start of the Gallic Wars the Helvetii were completing the planning and provisioning for a mass migration west.

After a series of failed negotiations in which Caesar would have allowed the Helvetii to cross the Rhone and Roman territory on their way to the west coast, the tribe made several attempts to cross the Rhone river by force – each time being turned back by the Romans. The Helvetii then changed track and began moving west by negotiating with neighboring tribes and pillaging lands under Roman protection on their way to the river Arar (now named the Saône River). The river Arar is where Caesar eventually caught up to them. In the end and with massive loses on both sides, the Romans were victorious and accepted the Helvetii’s surrender (executing more than 6,000 soldiers who attempted to flee rather than surrender). In the Commentarii de Bello Gallico Caesar refers to a Greek census from that time which reported the Helvetii population as 368,000; only 110,000 survived to return to their homeland.