Today, feminism is often associated with the political protests of the 1960s or the earlier women’s suffrage movement, but Stanford historian Paula Findlen’s latest research reveals that the impetus to champion women started in the late Middle Ages.

Today, feminism is often associated with the political protests of the 1960s or the earlier women’s suffrage movement, but Stanford historian Paula Findlen’s latest research reveals that the impetus to champion women started in the late Middle Ages.

da ![]()

A scholar of the Italian Renaissance, Findlen has collected biographies of medieval women, written in Italy from the 15th to 18th centuries, several centuries after the women lived.

Through a close examination of these texts, Findlen found that these early modern writers were so passionate about medieval women that they sometimes fabricated stories about them.

As Findlen carefully tracked down the claims in these stories, she found they varied from factual to somewhat factual to entirely false.

These invented women were often mentioned in regional histories, with imaginary connections to important institutions. They were described as having law degrees or professorships, claims that turned out to be fictitious.

Findlen argues that these embellished tales represent what could possibly be described as the origins of a certain kind of feminism. “Early modern forgers used stories of women to create precedents in support of things they wanted to see in their own time but needed to justify by invoking the past,” Findlen said. “While debating the existence of these medieval women, the writers also contributed to the science of history as we know it.”

Expanding her archival base from Bologna to other Italian cities, and observing how these stories traveled beyond Italy, Findlen found that the stories of local women gained international recognition.

Findlen described her foray into conjectural history “a project partly about how early modern medievalists invented the Middle Ages, claiming and defining this past.” She added, “Making up history is a way of ensuring that you get the past you want to have.”

In her forthcoming publication, currently titled “Inventing Medieval Women: History, Memory and Forgery in Early Modern Italy,” Findlen pays particular attention to Alessandro Macchiavelli, an 18th-century lawyer from a Bolognese family.

Macchiavelli was passionate about finding evidence to support Bologna’s reputation as a “paradise for women.” He created stories and footnotes about learned medieval women from the region, including writer Christine de Pizan.

According to Findlen, “He aggressively made up [biographies of] medieval women and supplied the evidence that was missing for them.”

Presented as facts, these fables forged the medieval origins of Bologna’s female intelligentsia. Findlen initially worked on this material because she was searching for – and failing to find – evidence of medieval precedents that kept being invoked in early modern sources. “In the end,” she said, “it intrigued me.”

While people later recognized that Macchiavelli was a forger, it was true that he brought critical attention to women’s lives.

In a sense, Macchiavelli demonstrates “a quirky early modern male version of feminism,” Findlen said. He also contributed to the beginnings of the discipline of medieval history. When he forged a document, he did so based on extensive knowledge of the archives and a fine understanding of historical method.

“Medieval history is one of the really important subjects where people develop a documentary culture during the late 17th and 18th centuries, and they begin to identify and select the documents that matter for defining the Middle Ages,” Findlen said.

Imagining the women of Bologna

Between the 15th and 18th centuries, Findlen said, representations of medieval women enhanced a city’s reputation.

For example, scholars in Bologna wanted to learn about its presumed tradition of learned women. They craved information about medieval women who could provide historical precedents for someone like Laura Bassi, the first woman who can be documented as receiving a degree and professorship from the University of Bologna in 1732. Having precedents made her seem like a reinvention of the old rather than someone threateningly new.

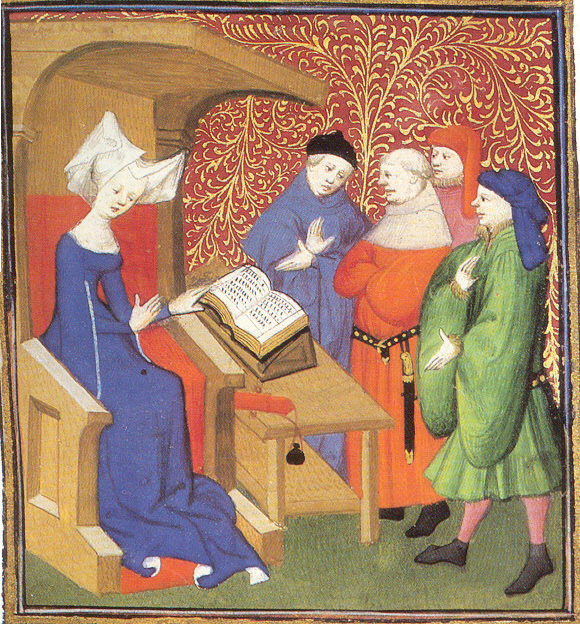

Findlen first turned to Christine de Pizan (c. 1364-1430), the daughter of a University of Bologna graduate and professor. She is perhaps best known for her writings praising women.

In her Book of the City of Ladies (1405), a catalog of illustrious women, Christine contemplated her Italian roots. This longing for her past inspired Christine to imagine “what the ingredients were of this world that made her, and other women like her,” Findlen said.

Although inspired by some kernels of truth, Christine’s writings invented evidence to fill out her narratives, Findlen said. In this way, Christine provides a starting point for Bologna’s interest in women’s history that will unfold over the next four centuries.

What we want from history

Findlen’s project rethinks our compulsion to write about the past. “Some of the stuff we take for granted is legend, not fact,” she said, “but I think that I’m even more interested in having people understand why we want it.”

Despite the presence of fake facts in medieval women’s biographies, Findlen emphasized that “the unreliability of the past is also part of the evidence that we have to account for.” Moreover, she added, this project requires “knowing the archives … well enough to catch the nuances.”

“The process of creating a history of women,” Findlen said, “starts with this impulse to create collective biographies in the 14th and 15th centuries onward.”

Envisioning the wider impact of her work, Findlen said: “I would like this project to offer an interesting window into the invention of history, taking Italy as a case study, to understand why [early modern] people were so passionate about the Middle Ages.”

During the Renaissance, “people are increasingly concerned with documenting the history that was,” Findlen said. “They’re interested in the history that might have been. And then they’re also interested in the history that should have been. And those are three different approaches to history.”